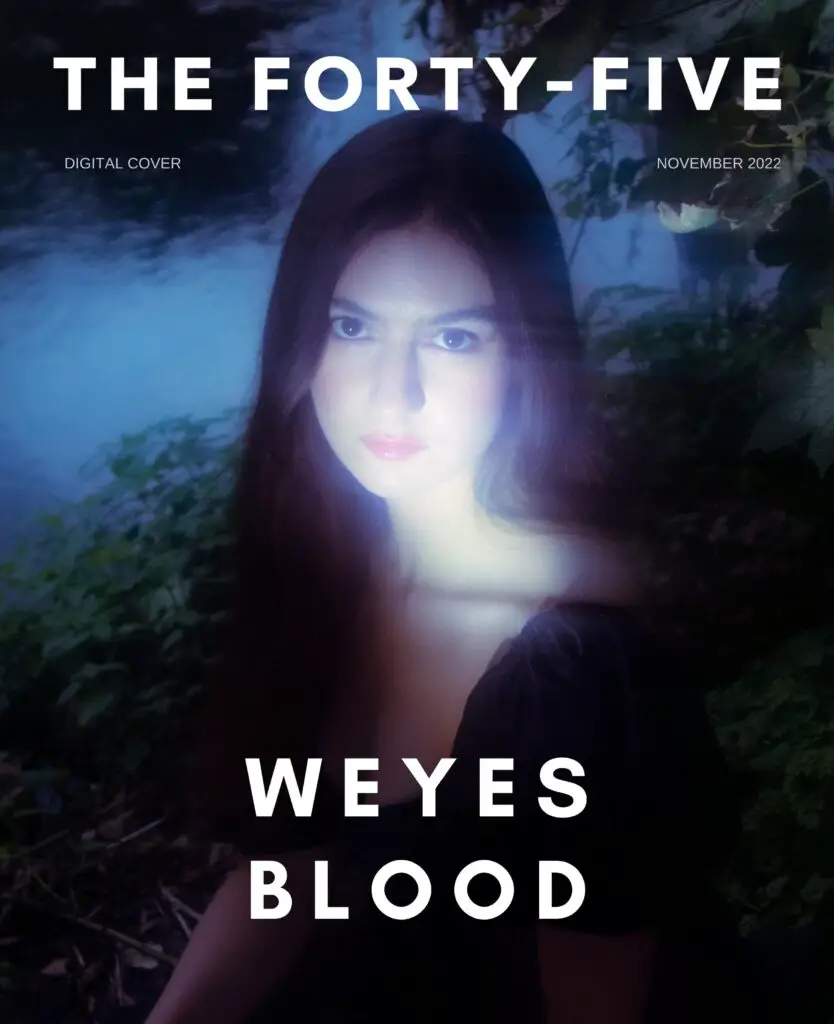

Weyes Blood

As Natalie Mering prepares to release the follow-up to her critically acclaimed album ‘Titanic Rising’, Celia Almeida uncovers the inherent darkness of Weyes Blood.

STORY: Celia Almeida. PHOTOS: Neelam Khan Vela

Natalie Mering is still singing about the end of the world.

“Living in the wake of overwhelming changes,” she sings on the lead single from her new album, ‘And In the Darkness, Hearts Aglow’. “We’ve all become strangers.”

On the phone with The Forty-Five ahead of the new album’s release, Mering ruminates on some of the factors that have led to the modern malaise she often addresses in her music and interviews. “We’re all kind of on our own algorithmic journey, for better or for worse,” she says with a slight chuckle, though she seems to come down on the latter, calling the effects “very polarising.”

“I think the difference between my generation and maybe my parents’ generation—I don’t think they felt as dystopian as we do,” says Mering. “Whether or not things have really changed all that much is up for debate, but I think it feels like it really has. It feels like things are really changing.”

The last time we heard from Mering, she was on the road in support of her breakthrough record, 2019’s ‘Titanic Rising’, her critically acclaimed fourth studio album under the moniker Weyes Blood.

Inspired by the tragic tale of the doomed ship (and the blockbuster 1997 film that reignited the public’s fascination with the real-life Greek tragedy), the album was widely interpreted as an elegy for Earth in the age of climate anxiety. The album cover depicts Mering submerged underwater in a childhood bedroom with art posters on the walls and a teddy bear floating in her bed. She stoically glares at the camera, her feet on the ground even as the water sweeps her hair straight above her head.

“A lot’s gonna change in your lifetime,” she warns on the opening track. “It’s high tide,” but she reassures, “you’ll learn to get by.”

No matter how many times she sang this meditation on tour, nothing could have prepared Mering or her audience for the global changes that would follow just over a year after the album’s release.

“We finished our last show on the tour in New Zealand the night before they banned gathering,” the Californian artist remembers. “I was in New Zealand and it was really chill, and then I went back to LA and it was like a total wild zone.”

The whole world came to a halt in those early days of the pandemic, and some people were paralysed right along with it – the isolation was crushing for the inhabitants of a planet already on shaky ground. Others threw themselves into work (if they still had it), perhaps as a way to mark time by progressing on creating something – anything, really. Mering went straight into the studio. By the end of 2020, an album began to take shape.

In mid-September, she announced the forthcoming release of ‘And In the Darkness, Hearts Aglow’, referring to the album as a “dystopian romance novel,” the second in a trilogy that began with ‘Titanic Rising’.

The album’s opener, ‘It’s Not Just Me, It’s Everybody’, expands on its predecessor’s cataclysmic themes through the lens of quarantine-induced isolation: “Mercy is the only cure for being so lonely,” she sings on the track. “Has a time ever been more revealing that people are hurting?” Put another way, as she sings near the end of ‘Titanic’, “It’s a wild time to be alive.”

Mering went into her 2020 writing sessions with the intention to create a more hopeful counterweight to the existential dread on her last album. “I wanted to make the record that was like the solution to the alarm, and all the uplifting kind of futuristic hope,” she says. “But I just felt like we were so in the thick of everything that was happening, that if I was gonna be really honest with myself, I was about to make a really subterranean, kind of intimate, vulnerable album… I do think some of the themes definitely continued, but it kind of got a little bit more intimate.”

Much has been made of her ability to put to music her generation’s fears and anxieties about a precarious future. But people sometimes miss how equally stirring it is when she sings about mini apocalypses; the everyday personal endings that can shatter a person.

Take the album’s gut-punching second single, ‘Grapevine’, an excruciating breakup ballad that previews the middle instalment’s shift from the macro to the personal, and from despondence to resignation. “California’s my body and your fire runs over me,” she sings of a former flame whom she calls an “emotional cowboy with no hat and no boots.” By the end of the song, the formerly entwined lovers are strangers once again: “Now we’re just two cars passing by on the Grapevine.”

In the song’s music video, a bloody Mering escapes the smoky wreckage of a car accident as her love interest, an amorphous shadowy figure with burning-red eyes lurks behind her, lures her to dance, and gets her back into the doomed vehicle, which crashes again. At the end of the visual, the beast lifts its mask and reveals the true monster: Mering herself.

It’s one of the many times she’s employed elements of horror in her work. The music video for ‘Titanic Rising’’s ‘Everyday’, the bounciest chamber pop track on an album of otherwise sweeping ballads, is a gory slasher short film. In the visual, Mering and her friends have a party, play spin the bottle, smoke some weed and make out before they’re stabbed and get their heads split open with axes.

“I like being a little tonally dissonant,” says Mering. “I think I’ve always been so enticed by the macabre because it was not allowed in my house, you know? We weren’t allowed to have horror movies and things like that. So for me, it was like very forbidden fruit. And once I could get into it and just find out how benign it truly is, that was really fun.”

I’ve always been so enticed by the macabre because it was not allowed in my house. For me, it was very forbidden fruit.

Weyes Blood

Mering was raised in a born-again Pentecostal Christian household, but she became sceptical of her family’s belief system in early adolescence, and she was vocal about it.

“I tried to get [my parents] on board with me,” she remembers. As she got older, she came to accept her family’s faith. “I never felt like they were the evil side of religion, you know? More like the communal side.”

Does her Pentecostal upbringing, with its inherent Biblical focus on the Apocalypse, factor into her fixation on the end times?

“Maybe,” she ponders. “But I also feel like the reason I talk about dystopia is because, over the course of my lifetime, I’ve just witnessed so many things shift and change faster than the public discourse can fully keep up with it.”

While modern dystopia is the primary inspiration for Mering’s thematic focus, she credits her rearing for igniting other fascinations. “I think my parents just kind of made me believe in things unseen… In some ways, Born Again Christianity is kind of New Agey in that way.”

She expands, “I feel like I took away an appreciation for stuff that’s beyond the logical explanation of things, and leaving space for there being something more beyond our scope of understanding. Because I do think that we have a very limited understanding of the universe. And I think a lot of philosophies and esoteric thinkers – they do eventually kind of come to that conclusion that the more wise you get, the more you kind of realise that you don’t know anything. So yeah, I think there’s a bit of that that I’ve carried on with me.”

While she eventually came to understand her parents’ point of view, it took some time for them to appreciate Mering’s artistry when she got involved in Portland, Oregon’s underground experimental noise scene in the late-aughts, including her stint in a band named Satanized.

“I started out playing folk shows – just me and acoustic guitar unplugged, [singing] really pretty folk songs. But it just felt like, at that time, noise was the frontier of new music… I discovered how exciting it was and then kind of got addicted to it, and eventually blended the two. I’d play my acoustic folky music with noises behind it, you know? And then it became Weyes Blood, what it is now.”

Her parents – both musicians themselves – didn’t get it in the early days. “They didn’t really like my music very much,” she remembers, “so I don’t think they wanted me to do it. There was not a lot of support.”

But they came on board as her music began to shift toward the expansive psychedelic indie folk rock for which she’s now known. They saw her play in “a real venue with a real sound system and a real audience” on the supporting tour for 2014 album ‘The Innocents’. “I think when they saw that I did have a music career, indeed, that was real, they were relieved and really impressed.”

Mering’s celestial voice draws frequent comparisons to Karen Carpenter, and the melodies on her last album recall another artist for whom mysticism loomed large: George Harrison. But despite sounding like she could have been plucked out of the ‘70s singer-songwriter and psychedelic movements, Mering continues to be deeply inspired by experimental noise music. But she acknowledges, “for the most part, I just was always better at making beautiful music versus harsh, loud, angry music.”

I was always better at making beautiful music versus harsh, loud, angry music.

Weyes Blood

One of her heroes has made note of her experimental bona fides. She recently collaborated with John Cale on ‘Story of Blood’, the lead single from the legendary Velvet Underground musician’s forthcoming album, ‘Mercy’ – his first album of original works in a decade.

The two first met when Mering interviewed Cale ahead of a reissue of his 1992 album, ‘Fragments of a Rainy Season’. Her reverence for his work was instantly apparent.

“I think I asked him so many questions that were so funny and specific to how big of a fan I was of that world and that scene,” she remembers. “He knew that I had a lower voice and he heard my music, and then when we jammed together, we were both so happy that we could create something that was cool. And [‘Story of Blood’] evolved a lot. When I first recorded on it, it was completely different. He just manipulated it and did all this crazy stuff to make it sound as unearthly as it does. So he’s a wild guy, and it felt like a big milestone for me. I’m a huge fan.”

Though her work with Cale signals one of the many musical routes she’s adept to take in the future, Mering felt she wasn’t finished telling the story she began on her last album. The second track on ‘…Hearts Aglow’, ‘Children of the Empire’, is a holdover from the ‘Titanic Rising’ sessions.

“I think [the trilogy] started unravelling for me as I started writing,” she says. “I also didn’t want to go on some crazy departure and just make a completely different album, because I still had some songs left over from the ‘Titanic Rising’ batch and I was just kind of still in that head space.”

Mering has already started writing the third instalment. There seems to be an element of compulsion to work through these themes not only for herself, but for the world that’s listening.

“I would like to think that my music is, as opposed to being entertainment, it’s more like enchantment,” she says. “It’s more about opening your eye and making you think a little bit, versus escapism.”

But people do need escapism to transcend pain, she adds. “Throughout the history of mankind, there’s always been these huge catastrophic cataclysms. So it’s [about] learning how to not underplay what’s happening – because I think we all need to mobilise – but also to understand that this is also just a part of being alive. And I think music is really good at that.”

‘And In the Darkness, Hearts Aglow’, is out on November 18.

Like what we do? Support The Forty-Five’s independent editorial with a monthly Patreon subscription. All contributions go back into funding our writers and photographers.

Become a Patron!